WELLINGTON COUNTY – The war that shook the world to its foundations from 1914 to 1918 was traumatic not only for the soldiers in the trenches, but also for the families and communities that awaited their return.

Weekly newspapers documented the struggles on the home front and the victories of community spirit that brought the nation together.

On Nov. 17 at 2pm, Wellington Advertiser reporter Phil Gravelle will examine the wartime role of local newspapers in a presentation to the Wellington County Historical Society.

The event will also include a display of artifacts and photos from the era, with a presentation by county councillor Jeff Duncan, as well as time for discussion.

It will be held in the Aboyne Room at the Wellington County Museum and Archives on Wellington Road 18 in Aboyne. Admission is free.

With radio still in its infancy, newspapers were the information lifelines for every community – as well as small businesses that had to generate revenue in order to survive.

As will be shown with projected newspaper clippings, the Great War provided the most dramatic content imaginable, with weekly battlefield accounts that stressed victories and tales of the determination and heroism of the fighting men.

In willing cooperation with government censorship and the patriotic line, the local newspaper was not a forum for discussion about the war. The international and national war news was printed as supplied.

At the local level, it was all about family connections, food and fuel supply issues, community events, fundraising concerts, war bonds, donation of supplies and convincing ever more men to volunteer for service.

In letters that came home from the front, often published on the front page, communities found their sons to be shockingly nonchalant about the dangers they had survived and about the day-to-day work of killing.

Cecil Patmore of Elora wrote to his aunt: “Words fail to express this war. It’s nothing but murder. Perhaps you can imagine a shell of 1,400 lbs. bursting above a trench full of men. Shells full of bullets the size of marbles and pieces of steel, glass, etc. The strain on a man’s nerve is awful. This sure is a war of extermination.

“I just heard the crack, crack of a machine gun. The nearest sound I can give you like its noise is the noise your sewing machine makes when you are sewing fast. A funny comparison, eh? Ha! Ha! Just a passing thought of my kid days.”

Fred Gale of Erin wrote to his father: “So far I have escaped with only a slight wound, and the Fritz who gave me that paid for it with his life. Incidentally, I downed three during the first day’s fighting. Had some quite narrow escapes, but managed somehow to come through OK. It was sure some novel experience going over the top for the first time. We had a dandy barrage covering our advance and it sure put Fritz out of business.”

Hugh McMillan of Erin wrote to his mother: “We’ve been furnished with respirators today to protect us from the gas. It is awful stuff and anyone who gets a dose of it has an awful death.”

Dr. N.C. Wallace of Alma, working at a Canadian hospital in Shorncliffe, England, wrote in the summer of 1915 to Mrs. H. Wissler, president of the Women’s Patriotic League in Elora: “The stream of wounded coming across never ends. The worst of it is that there is no hope of it ending for a long time to come. They are preparing for another winter in the trenches.

“Our poor fellows have suffered terribly, but they have won everlasting fame. Nothing is too good for the Canadians now. I am sorry to see by the Elora Express that two of the Elora boys have fallen on the field.”

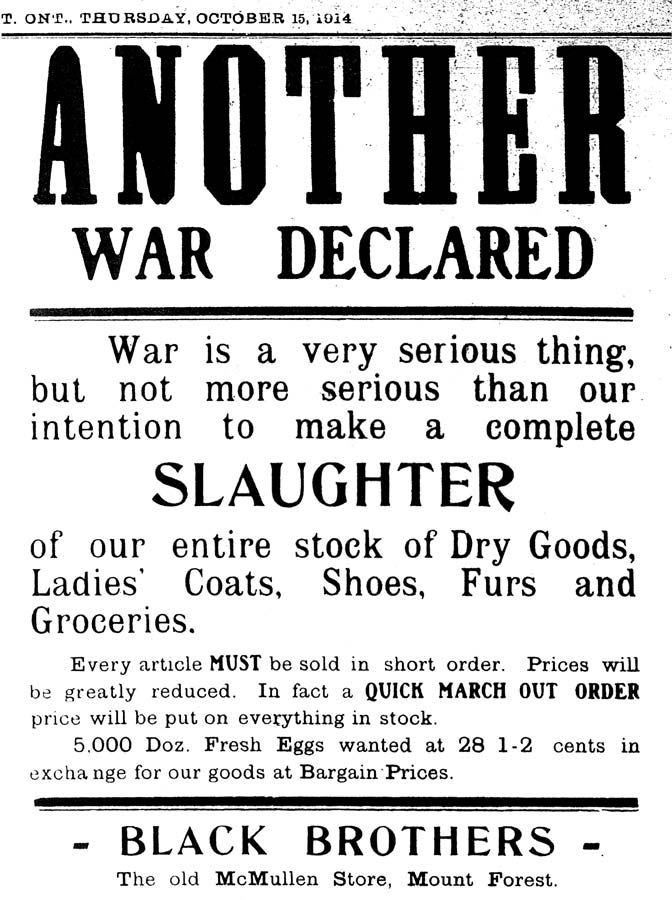

Also disturbing, though perhaps not shocking, were attempts by local businesses to use the war in advertisements, especially during the first year, when the full horror of the conflict had not sunk in.

An ad from the Black Brothers store in the Mount Forest Confederate said, “War is a very serious thing, but not more serious than our intention to make a complete SLAUGHTER of our entire stock of Dry Goods, Ladies’ Coats, Shoes, Furs and Groceries … In fact a QUICK MARCH OUT ORDER price will be put on everything in stock.”

The Carmichael store in Hillsburg (no “h” on the end of the village’s name in those days) ran an ad in the Erin Advocate: “Shot to Pieces! are the Prices on these Goods for Saturday, Nov. 14, and the only thing that remains are the Good Goods at ridiculous Low Prices.”

Early in the war, Wellington villages joined a massive grassroots effort in Canada and elsewhere to help the people of Belgium. The Germans had responded to resistance in the neutral nation by killing, torturing and deporting thousands of civilians; destroying churches, cultural treasures and thousands of homes; and refusing to provide food.

Imagine the shock when the Erin Advocate reported that a local pastor – an American who had lived in South Africa – claimed that England had perpetrated even greater atrocities against civilians in the Boer War (1899-1902).

Despite later denying the comments, Pastor Frederick E. Hedden, a conscientious objector, was arrested by the Dominion Police and hauled off to Guelph to face a charge of sedition. The crown dropped the charge on the condition that Hedden return to the U.S. for the duration of the war.

As published in The Erin Advocate.

Publisher Wellington Hull said, “This community will not stand for any more of this kind of talk.”

The scandal – well known in England, but not in Erin – was that the British, in response to Boer guerrilla tactics, had in fact burned farms, poisoned wells and rounded up civilians (mainly women and children) into concentration camps.

The families of men still fighting received smaller rations. An estimated 26,000 died in these camps due to malnutrition and disease.