The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

Last week’s column dealt in part with the Louden Machinery Co. of Guelph, which was a major supplier of barn stabling equipment in the 1910-1930 period.

Wellington County led Canada in these years in the manufacture of metal stabling and mechanized barn equipment, with three major firms. Dominant by far, and longest lived of them, was the Beatty firm of Fergus. The third was the upstart Superior Barn Equipment, also of Fergus.

The first two decades of the 20th century were good ones for Ontario agriculture, and in particular, the dairy industry. The output of dairy products more than doubled between 1910 and 1920, and a lively export market for beef and hams boosted the number of animals on Canadian farms.

Some farmers constructed new barns in this period, and others retrofitted their older barns with new equipment, saving labour with manure and feed handling facilities, and improving the housing of animals to keep them cleaner and healthier. These conditions provided boom conditions for makers of barn equipment.

George Maude, who founded Superior Barn Equipment, spent most of his life in Wellington County. He grew up on a farm in Puslinch. His father, William Maude, was a somewhat rootless Yorkshire man, skilled as a loom maker.

The family moved from England to the United States, and then to Canada, moving to the Ingersoll area, where George was born in 1882. Bill Maude eventually settled in Puslinch, close to the textile mills in Preston and Galt that provided him with employment.

As a youngster, George Maude showed artistic and inventive ability. In the late 1890s he went to Guelph and apprenticed as a tool and die maker at the sprawling Taylor-Forbes factory, which produced lawn mowers and a wide range of hardware.

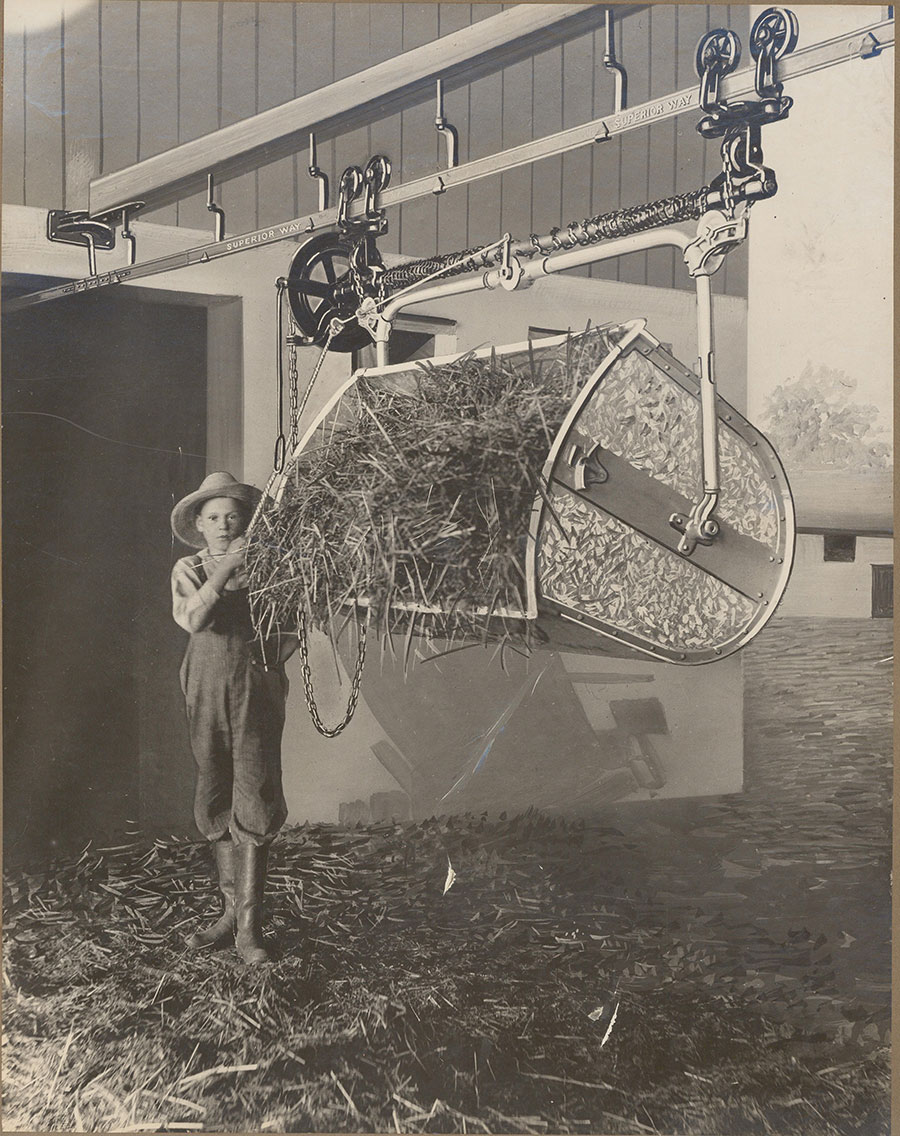

Around 1902, his training completed, young George moved north to Fergus and a position with Beatty Bros, at that time manufacturers of farm implements. The Beatty firm had gone through a bankruptcy in 1896, but at this time was rapidly rebuilding its fortunes. George’s inventive ability served the firm well: he helped design and build new products, among which were stabling and litter and feed handling equipment using an overhead monorail system.

Opinionated and strong willed, young George eventually crossed swords with W.G. Beatty, who was trained as an engineer and who headed the product development section. George Maude felt slighted when Beatty did not use some of his ideas for new products, and became particularly galled over W.G.’s habit of taking out patents in his own name, rather than that of the company or jointly under the Maude and Beatty names.

By 1911, he had enough. In the summer of that year George Maude, at 29, struck off with his brother Robert, and established Superior Barn Equipment as a partnership. The name was intended as a snub to his former employer, meaning “Superior to Beatty’s.”

The Maude brothers enjoyed immediate success with their lines of stanchions, stable equipment, metal pens and stalls, litter and feed carriers, and water bowls. There were several skirmishes with the Beattys over designs and patent violations, but George Maude survived them all.

Their father, Bill, soon moved to Fergus, working as a pattern maker. Aware of the importance of advertising and promotion, George issued two-colour catalogues promoting his products, and peppered his ads with slogans such as “…a stable that will make drudgery a pleasure and help to keep you boys on the farm.”

After five years of growth, and suffering cramped working conditions in make-shift facilities, the Maudes purchased the old Fergus Cold Storage building, a modern industrial building on the Beatty Line that had been constructed in 1902, and vacant for the previous three years.

The brothers asked for a loan from the town of Fergus, but failed to get one. The Beatty brothers campaigned vigorously, and successfully, against them in the referendum on the bylaw.

The Maudes managed without the loan, refitting the plant for their purposes. It was ideal: a modern one-storey structure, with railway sidings on either side, one for each railway. Month by month they added new equipment. The capital investment was reflected in their assessment: from $1,800 in 1916 to $3,275 in 1919.

Inflation after the First World War put a strain on the Maudes. Farmers wanted their products in record quantities, but the brothers lacked the cash to expand. The solution was incorporation.

The new firm, Superior Barn Equipment Co. Ltd., issued 600 shares of preferred stock at $100 each to the public in 1919. The Maude brothers retained 1,000 shares for the value of the factory, stock and equipment in the old partnership.

The incorporation provided $60,000 of additional working capital, and the firm was sufficiently profitable to meet the 7% dividend guaranteed in the prospectus.

The Maudes remained firmly in control, with George as president and managing director, and Robert officially listed as treasurer. George’s sister, Edith, actually did much of the office and bookkeeping work.

Distrustful of outside investors, George encouraged his dealers to purchase stock in the company. He wanted ownership to rest with those who possessed a knowledge of agriculture and the cyclical nature of the farm equipment industry. He also tried to sell as much stock locally as possible.

Following incorporation, George set his sights on the American market, especially the midwest. He developed plans for a branch plant in Elkhart, Indiana, but nothing came of it, though he made many trips there.

With his strong opinions on every subject, and his lively, inventive mind, George gradually acquired a reputation as an eccentric. His appearance reinforced the notion: he was tall, perpetually wore a skullcap, and sported a beard in an era when these had become rare. Dubious of the concept of pasteurized milk, he kept a cow at the rear of the factory, and in summer tethered it on the right-of-way of the CNR tracks beside the plant.

By 1924, it was plain that the boom in barn equipment was over. The Maude brothers began scouting for other products to make, and settled on a three-legged stool, with an optional fold-down step. Within a few years the stool and chair business dominated production.

The new lines were not without problems. The major one was with Cedric Eason, who sold the Superior stools door-to-door. Soon he was buying them in large lots, and affixing his own labels to them: The Kitchenware Step-Stool Co., Fergus. Eason then went to the U.S., and secured American patents on the design, and then attempted to sue the Maudes for patent infringement.

In 1926, the Maudes began producing their popular Model 26 stool, available in five heights without a step, and three with the fold-down step. By the end of 1927 they had sold 60,000 of these. The barn equipment business eventually dwindled, and they sold this part of the business to the Beattys.

Of George’s three sons, only the eldest, Alister, joined the firm. Soon he was handling much of the sales work. One afternoon in the spring of 1931 he failed to return following a quick trip to the post office. That evening Alister was discovered dead of asphyxiation in his car, parked beside a road near Glen Christie. The evidence was ambiguous, but was it was probably a suicide. He was only 21.

Following the death of Alister, George’s innovative ideas dried up. There were no more new product lines or plans for further expansions. He eschewed war contracts through the Second World War, and continued to produce his solid and durable foot stools and office chairs into the 1950s.

When George Maude died in 1959 the company was in terrible financial shape, having lost money for years. But he retained the old name, Superior Barn Equipment, to the end.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on July 28, 2000.