The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

During the recent federal election campaign one feature of old time electioneering was absent: the big rally.

It was big news when a party leader drew more than a couple of hundred people. A generation ago, leaders frequently spoke to gatherings of 20,000 in the big cities, and sometimes a couple of thousand in smaller towns.

Gone even longer is the old-fashioned speaking tour between elections. Leaders down on their luck would often use those tours to rally their supporters, or to solidify support that was growing thin. Sir John A. Macdonald’s summer picnics in the 1880s were notable successes in that regard. At one of those picnics, The Old Chieftain spoke to thousands at Aboyne, between Fergus and Elora.

Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s tour of 1912 was a later example. In September 1911 Laurier, after 15 years in office, lost to Robert Borden’s Conservatives. Laurier blamed the unpopularity of his major plank, free trade with the United States, for the loss. But there were other factors. His administration seemed old and tired, and the party organization, complacent that victory was certain, mounted a pathetic campaign.

A year later, Laurier, rejuvenated after his post-election despondency, decided to undertake a tour of the Dominion. In August he was in the west. He tackled Quebec in September, then into northern Ontario, concluding in southern Ontario in October.

The reception he received in most places delighted him. The tour was to end in Guelph on Oct. 7, but party organizers later decided to move the last rally to Mount Forest. The Liberals had solid organizations in both Wellington North and Grey South. Jointly they formed a committee to plan the day, headed by J.J. Cook, mayor of Mount Forest and president of the Wellington North Liberals, and A.W. Wright, proprietor of the Mount Forest Confederate.

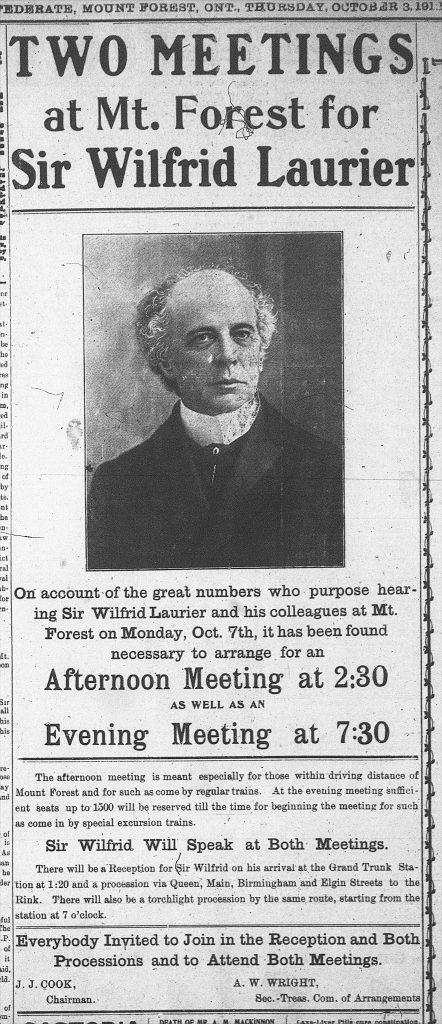

This notice was published in the Confederate four times in the weeks leading up to the visit by Wilfrid Laurier to Mount Forest in 1912.

Wellington County Museum & Archives

Along with Laurier, the touring party included three high-profile MPs: George P. Graham, Charles Murphy, and F.F. Pardee. Also taking part was the Liberals’ rising star, W.L. Mackenzie King. He had been Minister of Labour in the last Laurier cabinet, and after the election loss Laurier put him in charge of the Liberals’ national office, at the handsome salary of $2,500 per year. The Mount Forest committee added Hugh Guthrie of Guelph to the lineup.

Wright, with his connections to editors across the region, did everything possible to publicize Laurier’s visit. In his own paper he ran a large portrait of Laurier four weeks in a row. The committee anticipated thousands of visitors, and that called for careful planning. Cook and Wright chartered special trains on the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific, to bring in people from Owen Sound, Guelph and Durham. They booked both the skating rink and the town hall. Two weeks before the big day they decided to add an afternoon session of speeches, and asked local residents to attend that one in order to leave plenty of room for those coming by train in the evening.

Cook, Wright and others on the local committee were frantic with last minute preparations on Oct. 7. They spent the morning putting up flags, bunting and banners along Mount Forest’s main street. A novelty was an electric sign saying “Welcome,” strung near the post office.

Sir Wilfrid planned to arrive in Mount Forest on the mid-day train from Palmerston at 1:20pm aboard his private car. Well wishers at Palmerston delayed him slightly.

The Lucknow Pipe Band was playing when Laurier’s train pulled up to the platform. Meanwhile, Cook and Wright boarded the train to explain quickly the local preparations to Laurier and his staff. A few minutes later Cook reappeared on the rear platform of Laurier’s car, with an brief welcome to the crowd, which included all the town’s school children and most of its adults. Then Laurier stepped through the door and replied graciously, punctuated several times with cheers.

Liberal Party workers quickly organized everyone into a procession: the two bands, school children with flags, and the visitors in motor cars. The parade set off on a circuitous route, via Main Street, to the arena.

Sensitive to local loyalties, Laurier asked someone to find Senator James McMullen, the local Liberal warhorse, before he entered the arena. To thunderous applause he walked in arm-and-arm with the Senator, who sat beside him on the platform. By then it was past the scheduled 2:30pm beginning for the rally.

Mayor Cook wasted no time introducing Mackenzie King. The future prime minister was a much more exciting speaker in 1912 than he was later in his career. King spoke longer than anyone that day, at both the afternoon and evening events. His voice was firm and animated, carrying easily to the back corners of the arena.

After a long-winded introduction, Laurier rose to speak, but first received bouquets from two girls, Mary Pickett and Madelene Broughton. Gracious as ever, Laurier stooped to kiss the girls. He also received a bouquet from the Women’s Institute. Laurier spoke easily and informally, but to those who had heard in years past, he was obviously past his prime. He had marked his 71st birthday earlier that year. He seemed a little tired, and his voice, though still pleasant in tone with his distinctive accent, could not be heard at all at the back of the rink. But most of those in the audience were loyal party supporters. And with no election on the horizon for another three or four years, the audience was generous with applause and cheering. The crowd, numbering between 2,500 and 3,000, was in a good mood. Many believed this was their last chance to see a Canadian political legend.

In addition to the special trains, both the Grand Trunk and Canadian Pacific added extra cars to their regular trains. Those brought large delegations from places such as Southampton, Orangeville, Teeswater and Erin.

The local committee planned a torchlight parade in the evening. Those plans turned into a disaster. So many people turned out that organizers could not shout instructions above the noise. Special trains from Guelph and Durham arrived late. Those responsible for bringing the torches took them to the wrong place.

No one seemed to know what to do or where to go, and with the scheduled starting time of 7:30 approaching, Mayor Cook decided to abandon the march and head straight to the rink. That disappointed the hundreds who were lining the streets, waiting for a parade that never came.

When the speeches began, a little late as might be expected, the rink was packed, literally to the rafters. Every seat was occupied, hundreds stood at the rear, and dozens of men sat on the beams supporting the roof. Estimates put the crowd as high as 5,000. Another 600 people were at the Town Hall. The committee had removed all the chairs there; everyone stood.

The speeches at the arena were similar to those in the afternoon. All the speakers shuttled between the two venues. Laurier began weakly, but seemed to recover his lungs in the second half of his speech, declaring that when he was returned to office he would pick up his old policies where he left off in 1911.

In both his afternoon and evening addresses, Laurier stressed the importance of the British connection and British institutions. He was still smarting at the accusations of Americanism hurled at him a year earlier, when he pushed free trade with the United States. Both times he ended his speech with a devastating attack on Borden’s first year in office.

The weakest part of the rallies was Laurier’s voice. He simply did not have the volume or projection that he possessed in his prime. Many in the rink who could not hear him began whispering to their neighbours. That caused some restlessness in the crowd, and more murmuring that further impacted on the ability of the great statesman to be heard. There were few hecklers, and they tended to be men who were the worse for liquor. Liberal workers assisted the Mount Forest constable in ushering them from the arena.

The more cautious estimates put the combined afternoon and evening arena crowds at 8,000. The Toronto Globe’s guess was that 10 or 12 thousand people were in town. Liberal organizers described Laurier’s Mount Forest appearance as the best organized and most enthusiastic of the entire tour. The Conservative Drayton Advocate thought there might have been 10,000 people in Mount Forest that day. While Liberals rejoiced, more impartial observers viewed the rally as a farewell appearance by the Old Warrior. And more than a few Liberals thought they saw the future of their party when the youthful and energetic Mackenzie King addressed the crowd.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on Feb. 24, 2006.