Resident dies after Saturday house fire

Fire marshal, coroner investigating after 75-year-old found inside Minto home

Latest Posts

Arts

High school Black Student Union organizes show to celebrate Black legacy

Show to include student talent, professional performers

Sports

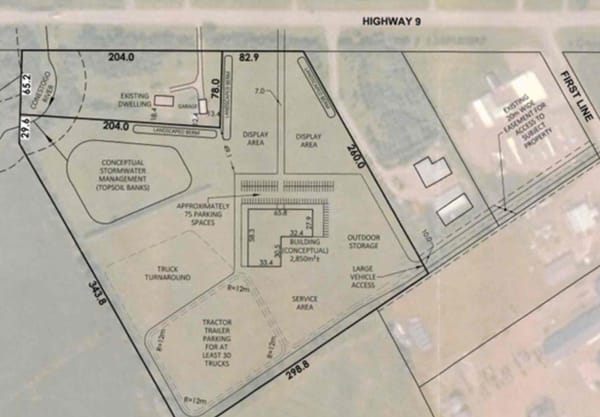

New lacrosse club searching for players across southern Ontario

Southern Ontario United Lacrosse Club will be based in Marden