HARRISTON – The days are long and the work strenuous, but here, there are no bombs falling from the sky.

Harriston is a long way from the refugee camps of Turkey, crammed with displaced Syrians, and farther away still from Aleppo’s embattled streets. But for Obid Almohamed and his family, the small community of Harriston, with less than 2,000 inhabitants, is now home – and Canada, their country.

Obid, his wife Nizal Alobid and their five children became some of Canada’s newest permanent residents when they arrived nearly a year ago at Pearson International Airport in Toronto on Nov. 23, embraced by Obid’s brother Ahmad Almohamed.

It had been over five years since the brothers had last seen each other after escaping a civil war in Syria that continues to this day.

A mere day after arriving, Obid was put to work with little more than a day’s rest.

Ahmad cracks a large smile and laughs at the thought.

“He basically rested for eight years” while in refugee camps, Ahmad joked during an interview at the home where Obid now lives.

A 2017 story in the Wellington Advertiser about Ahmad, a Syrian tile-setter who wandered for years through Turkey’s refugee camps with his family in tow before being brought to Canada by the Minto Refugee Resettlement Committee, prompted Arthur-based CoverUps Flooring and Bath owner Gord Blyth to offer him a job.

Now, Obid and his eldest sons are also employed by Blyth.

Blyth had a major role in Obid’s resettlement, guaranteeing him employment and a home for his family, as the Presbyterian Church of Canada worked to help Knox Calvin Presbyterian Church and the Minto Refugee Resettlement Committee sponsor the family.

Krista Fisk, a local realtor and resettlement committee member, had a lead on a house.

Blyth and Ahmad toured the house on a weekend and received word the following Wednesday their joint offer on the house had won.

“Within one week we had a home for this family,” Blyth said.

One of the largest obstacles to a successful resettlement had been overcome and three weeks later, the family of seven would arrive.

The families at Pearson International Airport. Submitted photo

In an interview with a reporter about how Obid and his family are settling in to Harriston, Ahmad, who has developed a firm grasp on English over the past five years, translates for his brother.

Nizal serves Gató cake and harissa dessert with ceylon black tea (heavy on the sugar) at the family’s residence.

Nizal has decorated the room with her artwork – pieces of folded, decorative paper are fashioned into an unfurling centrefold in a book mounted on a corner wall with cascading vines carrying red, orange, and pink flowers.

Hanging from the ceiling is another artwork of newspapers folded into four stacked cones.

On a nearby couch sit Obid’s and Nizal’s sons – Mohamed, Omar and Ahmed – who appear to listen intently, despite not understanding English, while scooping bites of dessert pastry and sipping small glasses of sweet tea.

Nizal’s artwork. Submitted photo

Millions of Syrians have fled their homeland in the decade since Syria’s majority Sunni Muslim population began protesting against President Bashar al-Assad’s minority Alawite and Shia-Ba’athist Party in 2011, giving rise to brutal government oppression and a bloody and convoluted civil war propped up by competing international interests.

According to reports from a United Nations Human Rights Council commission, over 5.6 million Syrians have fled the country, and of those that remain, 90 per cent live in poverty and 14.6 million are reliant on humanitarian assistance.

A June report also notes “particularly abhorrent” civilian attacks “through air strikes, shelling, and the use of improvised explosive devices, often deliberately.”

Another reports a missile strike on an April morning that killed four boys, aged 12 to 14, as they walked to school.

When Ahmad heard the sound of a falling bomb back in Syria (he mimics a whirling sound) he felt scared, and his stomach ached – the physical manifestation of the anxiety from not knowing where the next bomb would land.

When the explosion happened, Ahmad recalls running outside to find smoke coming not from his neighbour’s home, but his own. “I understand at this moment a bomb come to my house,” he said.

He ran back inside to find a room blackened and full of smoke, and his three-year-old daughter and his first wife were dead.

Life in Syria was good before the war, the brothers say.

Ahmad smiles as he recalls late nights spent talking with Obid and drinking tea.

But where there is war, Ahmad said, it becomes difficult to work, find food and clean water, and access to medicine.

“After we left Syria,” he said, “wars, and wars and wars.

“Too many different scenarios happened.”

Ahmad says he doesn’t know who to blame for killing his wife and daughter, and for uprooting his family’s life.

“They all kill people; they worry about what they want, that’s it,” he said of the power-hungry groups who have reduced swaths of the country to rubble.

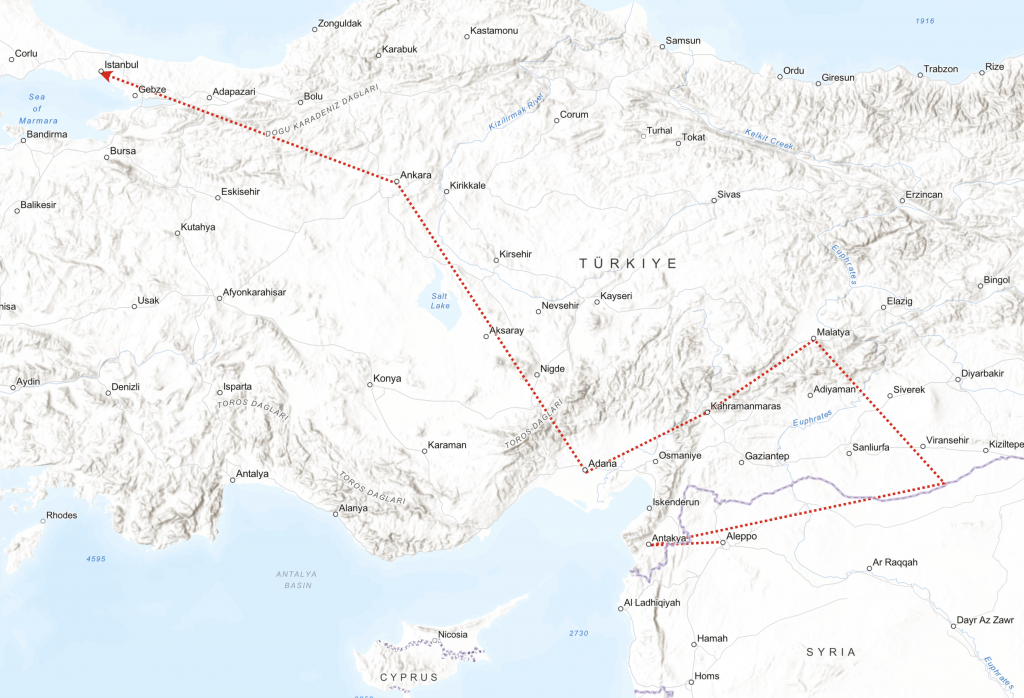

In 2013, he and Obid left most of their belongings behind, fleeing west with their families to the border of Syria and Turkey, where they crossed the Orontes River into Antakya, the capital of the southernmost province of Turkey.

“They take all your money to cross onto [the] other side,” Ahmad said of the crossing, made on a makeshift raft with empty barrels to keep it afloat.

Leaving Syria was “hard, so hard,” Ahmad said. “If God [would have given] me life, I would stay.”

Travelling north in Turkey, Obid lived for three-and-a-half years at a refugee camp located between Viransehir and Ceylanpınar before moving to a camp in Malatya.

The journey from Aleppo to Istanbul. Advertiser graphic

“We’re not allowed to work there if we live in [a] camp; they give us money, like a grocery card, but it is not enough to live,” Obid said.

While Ahmad began his new life in Canada in 2017, Obid and his family were languishing in Malatya.

The families communicated everyday through WhatsApp, and the Minto Refugee Resettlement Committee began the immigration process to bring Obid to Canada.

“You’d think the second time would be so much easier, but it was far more complicated,” said Terry Fisk, Krista’s husband and then chair of the resettlement committee.

“Your pitch had to be really strong.”

There was an incredible amount of paperwork and much emailing back and forth between different agencies – a time-consuming and cumbersome process hampered by the pandemic and stretching over several years.

In 2015, the federal government began working to resettle tens of thousands of Syrian refugees as part of its “Welcome Refugees Initiative.”

Between November 2015 and August 2022, according to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada data, there were 84,110 Syrian refugees who were resettled in Canada—of which 29 per cent arrived during a 100-day push in 2015-16 to resettle 25,000 Syrians here.

However, immigration was comparatively limited thereafter, especially during the first year of the pandemic, when, according to UNHCR data, Canada admitted just 9,200 refugees (the number of admitted refugees increased to 20,400 in 2021, but remained below a pre-pandemic level of 30,100 in 2019).

In the meantime, the camp in Malatya closed, and Obid’s family relocated to Kahramanmaras, where they stayed for less than a year.

Krista and Terry say the reason the family was eventually accepted is because of Obid and Nizal’s daughter Nor, who has cerebral palsy.

“They are very compassionate, and if there’s a child that’s suffering, or a child that could have a better lifestyle leaving there and coming here, then that moves you right up to the top of the list … I don’t think they’d be here if it wasn’t for their daughter,” Terry said.

The family in Istanbul before departing Turkey for Canada. Submitted photo

The resettlement group is obligated to sponsor the family for one year, ensuring they’re fed, healthy and housed.

But Krista said the journey endures long after their obligations officially end.

Terry and Krista continue to attend birthday parties and stay involved in the families’ milestones and daily lives.

“We’re really proud of them,” Krista said.

Ahmad believes Obid will have an easier transition because he already has family here. Ahmad arrived knowing no one.

“We have to work hard, [we have] no English, we come, we don’t have anything, and [it’s] cold, this is a big thing, no family, like very difficult,” Ahmad said.

Obid feels good being in Canada, and is happy his sons are learning tiling and trade disciplines.

Halal foods, permissible and processed according to Islamic law, are available in Listowel and Drayton, and the family have found the town’s predominantly white demographic to be receptive.

English lessons are taken at the Harriston library branch, and the families pray at the Palmerston and District Community Centre Complex.

Medical care for Nor is significantly better in Canada, and a local service club and farmer came together to build a wheelchair access ramp at the home this summer.

Harriston Legion Branch 296 donated $5,000 from its “Catch the Ace” gaming fund to cover building materials for the ramp and the replacement of an entrance to accommodate Nor’s wheelchair, all built by local farmer and carpenter Marte Pronk.

Obid hopes to eventually purchase his own home, once he pays off his car – a statement causing laughter in the room.

He wants the community to know his family members are hard workers who desire to be self-sufficient and find independence – they’re not here for handouts.

Nizal hopes to continue learning English, and to open a small business selling her artwork.

From a refugee’s perspective, Ahmad said, the biggest challenge is learning a new language.

If Obid understood English, his brother said, more doors would open. For now, he feels at a distance from society here.

Adjusting to a work-obsessed culture has also been a challenge.

“We can’t do anything because here, it’s just work,” Obid said, causing Ahmad to laugh. “No time here,” Obid adds.

The summers pass by quickly, and they’re surprised by the number of bills people have to pay. Despite the adjustments, life here is “way better” than it was in Turkey and Syria, Obid said.

After all, the family’s desires are no different from any other human: safety, food, housing and education.

Harriston is now home and the families will continue building their lives here, leaving the bloodlust of war and years of waste behind as a distant memory somewhere over the horizon.

“This is home; it doesn’t matter where you were born,” Ahmad said. “Who makes borders and citizens, just people.”

On Sept. 20, Ahmad and his six children received their citizenship certificates and are “extremely proud” to have officially become Canadian citizens.