FERGUS – An otherwise routine Thursday morning for retirees George and Dianne Fraser goes awry when their phone rings with distressing news their beloved grandson is in handcuffs.

George is an avid outdoorsman and hunter at age 69, but complications from diabetes means walking isn’t as easy as it used to be, and most mornings are spent sitting and watching the news.

His wife, Dianne, who is 71 and recovering from a recent hip replacement, takes a break from scrolling through updates about The Young and the Restless on her tablet to answer the ringing home phone.

A voice on the other end says its Charlie, their 17-year-old grandson, and George can hear Dianne telling him to stay warm and eat chicken noodle soup.

Charlie is technically deaf and rarely talks on the phone, but George hasn’t talked to his grandson since November and joins the call to hear that being sick is the least of his worries.

Charlie has been arrested after the car he was a passenger in was pulled over by police and a large quantity of drugs found, the grandparents are told.

A judge-imposed gag order is in place, the voice says, trying to prevent George and Dianne from telling anyone else about the situation.

George is told to call another number to speak with an empathetic OPP sergeant, who is willing to pull some strings to get Charlie freed that day — but there’s a catch.

A bail bond will have to be paid first, and George must deposit $8,500 cash in an envelope for a courier to pick up.

* * *

Something admittedly seems off about stuffing thousands of dollars into an envelope and handing it to someone, but George is used to helping his grandson navigate difficult situations.

How do I pay this? he thought.

But a call to a lawyer friend, who is adamant George is being had, shocked him.

“It can’t be a scam, they’ve got too much information,” he said, pushing back.

The voices on the phone seemed to know everything about his family, down to the street names where he and Dianne, and Charlie’s family live.

George’s next call was to the OPP. A call-taker also tells George he’s being scammed, and suggests contacting Charlie.

After reaching Charlie’s mother Jacqueline, who confirms Charlie not only isn’t sick, but is behind the wheel learning to drive, George at last concedes he’s being scammed — and decides to scam the scammer.

If they’re dumb enough to send somebody here, I’m going to have the police here to arrest them, he thought.

Police tell George not to open the door, and to stop responding to the scammer’s demands.

“No, this guy’s coming to my house,” he said, making it clear that if police aren’t coming, he’s going to handle the situation himself.

* * *

George is sitting when the doorbell rings, and as he moves to put on his shoes, Dianne opens the front door to their Princess Street house, inviting the purported courier into the narrow hallway.

A surgical mask obscures most of the person’s face, which is also covered by a hoody tightened around his head.

Only a pair of peering dark eyes and a large pimple on the person’s forehead are visible as George approaches.

Reaching behind the front door, opened alongside the hallway wall, George reveals a baseball bat, telling the slender person not to move an inch.

For what feels like minutes, George talks to the person, their body shaking and eyes darting, as Dianne calls police.

Three OPP cruisers come to a halt in front of the Fraser’s home shortly after 1pm on March 2 – two days into Fraud Prevention Month.

The officers are shouting and running, quickly closing the gap between the sidewalk and the Frasers’ porch where George has hustled the person to.

Stop where you are, put your hands behind your back, police command.

‘I just wanted this guy to get caught’

George is adamant he’s “just an ordinary grandparent” and only agreed to speak to the Advertiser about the couple’s “tremendously stressful” experience so the community and his older peers know more about how grandparent scams work.

Police warned against George’s tactics, but not one to be intimidated, he says he would do it all again.

“I felt what I was doing was to the benefits of the police and for everybody else that’s my age,” he explained.

“I just wanted this guy to get caught.”

Wellington OPP arrested Guelph residents Efeson Tesfaalem Teklehaymanot, 20, and a 17-year-old who cannot be named under the Youth Criminal Justice Act, in connection with the scam.

Both have been charged with fraud over $5,000, according to police, and are to appear in Guelph court.

$1.34 million lost to fraud in Wellington County

In 2022, the OPP responded to 348 incidents involving “emergency scams” across the province, up from 108 emergency scams in 2021.

According to police, many of the complaints originated in Lambton, Essex and Oxford counties.

Though fraud data in Wellington County goes beyond grandparent scams, Wellington OPP media relations officer Jacob Unger wrote in an email that police here have received 86 complaints of fraud since the end of December, amounting to a reported loss of around $1.34 million.

Wellington OPP have recorded 1,647 fraud-related calls since 2018, according to Unger.

Charges have been laid in connection to only five per cent, or 84 of those calls.

Many investigations are ongoing, Unger added.

The average financial loss ranges between $5,000 and $15,000 per complaint, Unger stated, with some outliers ranging into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Evidence gathered by police usually results in warrants being written, Unger explained, adding police coordinate in their investigations with other specialized OPP units, and organizations such as the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre and the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada.

Methods such as spoofed numbers or prepaid calling cards are used to intentionally thwart police, Unger stated, making for complex investigations that may take years to shake out.

“I was just notified [on March 16] that a warrant for the arrest of two individuals was issued relating to a fraud investigation that began in July 2021,” Unger stated.

But even when charges are laid, the chance of recovering fleeced funds is slim, often leaving victims empty-handed.

So police are focusing on education and prevention, including encouraging bank tellers to pay attention to seniors withdrawing large sums of money.

‘I’m so afraid to trust people’

George remains shocked at how much accurate information callers had about him and his family, and suspects much of it was found on Facebook.

“These guys have so much more information on you than you realize,” he said.

“They had me so completely duped.”

George fears seniors may be more vulnerable to scams, and said there’s a lot to lose, especially for those living on fixed incomes.

“I never acquired a lot of money though my life,” George said.

In addition to Dianne’s pension, he survives on a reduced Canada pension and old-age security.

“(So) $8,500 is a huge amount of money to me,” he said.

Although the Frasers haven’t lost a cent to the scam, there’s a lingering psychological toll.

“You gotta be so diligent,” George said.

“I’ve gotten to the point where I’m so afraid to trust people.”

‘Emergency scams’ cost Canadians $9.2 million

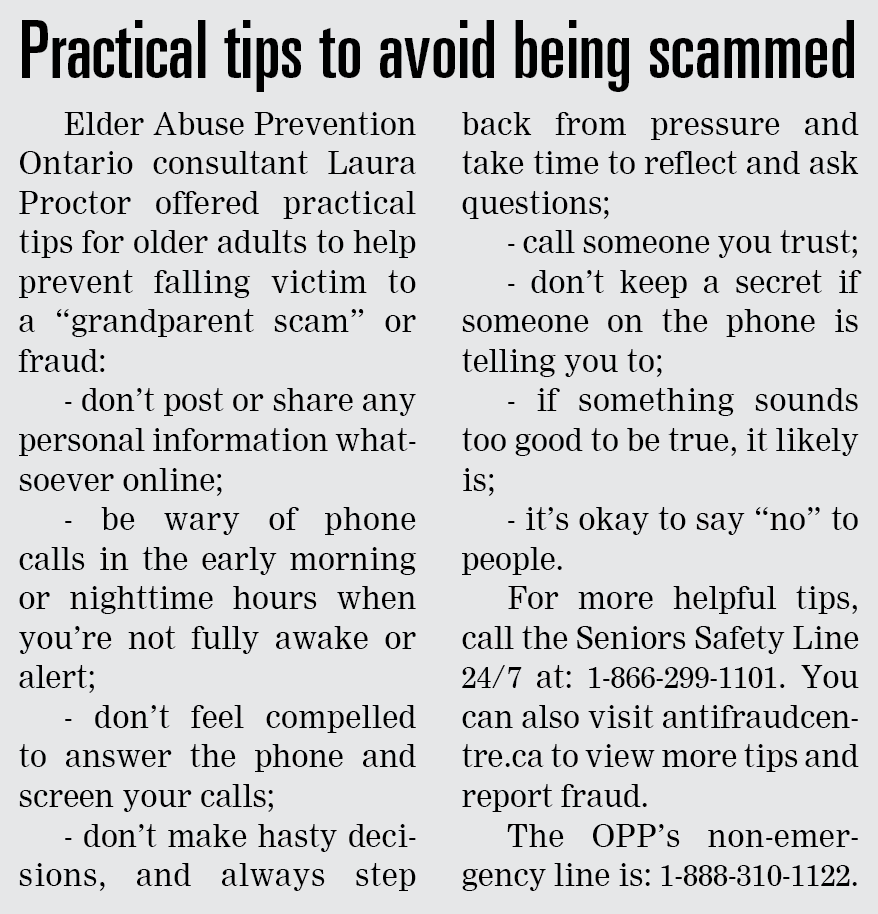

Elder Abuse Prevention Ontario (EAPO) consultant Laura Proctor told the Advertiser older adults are targeted precisely because of their trust in others.

“They were raised to respect authority and follow instructions, so that’s exactly what they’re doing when the fraudsters are calling and telling them some elaborate story of their loved one getting charged,” Proctor suggested.

The EAPO has observed an “ongoing uptick” in scams targeting older adults in the past three years, Proctor said.

She attributes the trend to seniors being more isolated throughout the pandemic, and the simple fact they’re more likely to answer a phone.

By the time seniors are reaching out to the organization, the damage is already done, Proctor said, adding that in some situations, seniors have taken out loans or gone into debt to satisfy fraudsters’ demands.

Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre data suggests the financial loss from emergency scams, such as the one George was subjected to, amounted to $9.2 million in 2022, nearly four times the 2021 total of $2.4 million.

But fraud is vastly underreported, according to the centre, which estimates between 90 and 95% of incidents go unreported.

George told the newspaper better education is needed for seniors, not only about how to handle scams as they’re happening, but also about the Canadian justice system — one which, unlike the United States, doesn’t require a bond to be paid to be released on bail.

Proctor of the EAPO agrees, going a step further, to say the targeting of seniors and lack of community resources is evidence of an ageist culture.

“When we don’t care about a whole segment of our population, they’re at a much higher risk of suffering a fraud or a scam,” she said.

Emotions of guilt, shame and fear are overwhelmingly present in the seniors she speaks with.

“They are so embarrassed, they are paralyzed with the fear that if they do tell their family, their family is going to take away their decision making; their competency is going to be questioned,” Proctor explained.

A cultural shift away from writing seniors off, to well-funded prevention and education initiatives is needed, Proctor said, if communities truly want to see more frauds prevented and reported.

Such a shift benefits everyone, she said, adding that in the end, we’re all getting older.