The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

No one can seriously claim that Rockwood was ever a hive of industrial activity.

Nevertheless, the village has seen a sizeable handful of industries over the decades. I described the shortest lived of them, the battery factory, several months ago.

This week I will take a look at the largest of them, the Harris woolen mill. The ruins of this enterprise are a major and to most visitors, a mysterious feature of the GRCA’s Rockwood conservation area.

The Harris family has a longer association with Rockwood than anyone. The patriarch of the family, John Harris, was the first settler there, coming in 1821. Fire destroyed his first cabin, and he subsequently spent several years teaching school in York County. He returned to Rockwood in 1829.

His life to that time had been an adventure. He was born in 1789 to an English family that had migrated to Ireland with Cromwell. He became a sailor as a young man, and was taken prisoner by the French during the Napoleonic Wars.

In Rockwood he married Jane Wetherald, sister of William, the founder of the famous Rockwood Academy. The couple had seven children, most of whom figure in the history of Eramosa Township.

The eldest son, John R. Harris, established the woolen mill in 1867. His father had died 10 years earlier, when John R. was only 20, and consequently he shared in some of the responsibility in raising his younger siblings. This experience strengthened his leadership qualities and enterprising nature.

John R. Harris established the woolen mill as a family partnership, with his younger brothers Thomas and Joseph. Some sources claim that John’s uncle, Thomas Wetherald, was involved with the business in its early years. The Wetheralds, it appears, had been involved with the textile industry in England.

The site for the mill was a piece of land on the southern, or downstream side of Rockwood, where the Eramosa River offered a power potential. Owner of the property was Henry Strange, the well-heeled Rockwood surveyor, speculator and developer. Though the Harris brothers built and started operating the mill in 1867, they did not complete the purchase of the property until 1872. It is entirely plausible that Strange was a silent partner in the firm at its outset, and a source of some of the original investment capital.

Markets were good for the blankets and course tweeds turned out by the Harris mill in the early 1870s. The brothers borrowed $3,000 from Thomas Easton in 1873 to finance an expansion of the mill. The early 1870s were the most profitable years that small Ontario woolen mills would see. Competitive pressures in the later decades of the 19th century forced smaller operations to become more efficient or to seek niche markets.

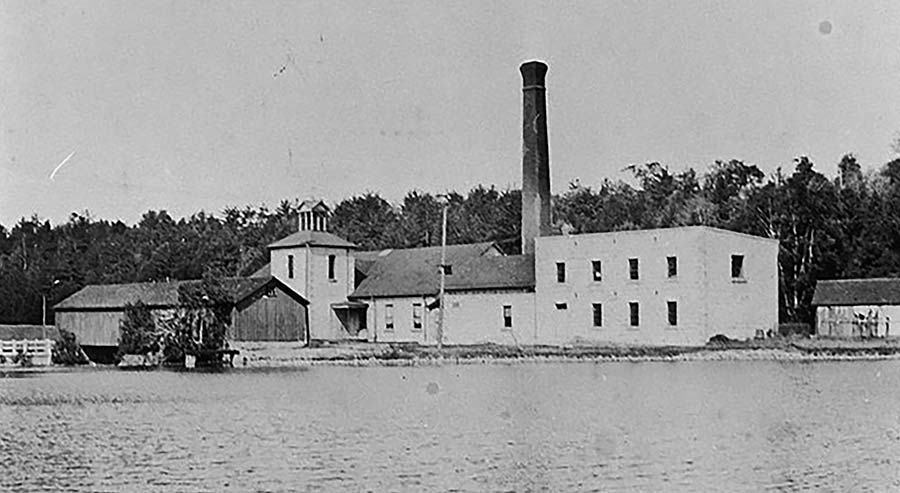

Over the years the Harris brothers made additions to the mill. The result was a rambling complex of buildings and additions, typical of enterprises that grew slowly by employing self-generated capital for expansion. John Harris decided to concentrate production on lines of blankets, coarse tweeds, and yarn.

The Harris mill experienced a major fire in the early 1880s which destroyed the original wooden mill, and damaged other buildings. For a time, beginning in 1883, some of the operations moved to the Rockwood Academy, owned by the Harris in-laws. It had closed as a private school the previous year.

The 1880s ended with John R. Harris as the sole owner. Joseph sold his share to his brothers in 1881, and Thomas turned over his share to John in 1887, taking back a mortgage for $10,000. This would suggest that the brothers valued the business at $20,000, a considerable sum for a textile operation in this period. In 1890 John refinanced the business again with mortgages of $3,000 to James Benham and $6,000 to his brother Tom.

After his brothers left the firm, three of John’s sons joined it. William eventually assumed the duties of general manager from John. Charles eventually became the plant superintendent. After a brief career in the flour milling business in Hespeler, Edwin Harris also joined the firm.

Few details of the operation of the firm in the 1880s and 1890s have survived. Employment hovered in the 30 range. John Harris provided some company housing by constructing five small frame houses near the mill on Valley Road. These were tiny by modern standards: about 24 by 16 feet. All were dismantled long ago.

With water power unreliable for year-round production, John Harris added a boiler and steam engine. The boiler had an additional use in providing hot water for the washing and dyeing processes. A massive brick chimney, perhaps 75 or 80 feet high, was part of an upgrading of the power plant around the turn of the century. The addition of an electrical lighting plant in the early 1890s vastly improved working conditions and efficiency.

John R. Harris, the founder of the company, died in 1899. His four sons, William, Charles, Thomas and Edwin, inherited the property. They decided to form a joint stock company with themselves as the principal shareholders. The mill afterwards did business as Harris & Co. Ltd.

The new corporate structure permitted the brothers to sell more shares if they wanted to expand again. New woolens factories, such as Forbes in Hespeler and Penman in Paris showed that the industrial trend was to very large operations. As well, incorporation protected their own possessions in case of bankruptcy, a constant risk in the textile trade.

The Harris’s added new equipment to make the production of blankets and flannels more efficient. William began importing wool from Australia. He believed its texture was better than Canadian wool.

When Ontario Hydro brought its lines to Rockwood, the Harris firm connected. Niagara power was not only useful for lighting, but for power. A large electric motor could replace either the water turbine or the steam engine, and offered cost savings and further efficiencies.

Harris & Co. Ltd. was not a high profile firm. I have never seen an advertisement for the firm’s products, though there are a few blanket tags in existence that are now prized collectors items. The absence of advertising does not mean that the Harris brothers were poor marketers.

They may have produced orders under contract from other firms, and they might also have been exporting much of their production.

Yarns and flannels, of course, would be shipped to other manufacturers, not to the public. Wool blankets, at least, were sold in Ontario under the Harris name.

The best years for Harris & Co. Ltd. were those between 1915 and 1918, when the firm secured huge orders for blankets for the Canadian army. The labour force swelled to more than 70, and the mill, for a time, operated in round-the-clock shifts.

The road led steeply downhill for the firm after the 1918 Armistice. Cut-throat competition, inflation, and rising labour costs wiped out the profit margins. A flood of cheap woolens and cotton goods, marketed under national brand names, saturated the market. There was little room for a small operator like Harris firm.

The mill operated sporadically after 1919, and closed, seemingly for good, in 1925.

In 1930, William Harris purchased the buildings, machinery and remaining assets from Harris & Co. Ltd. for $6,000, and attempted to start up the business again on a small scale in partnership with his son Edgar. It might seem foolish to have taken this step at the bottom of a depression, but William had lived with the textile trade all his life and knew that sometimes it was profitable to buck economic trends.

In 1930, both raw materials and labour costs had fallen. This afforded an opportunity to elbow a path into the market.

William’s final attempt proved to be unsuccessful. He closed the mill permanently in 1933.

With the mill closed, William and son Edgar decided to turn the property, which totalled some 190 acres and included some spectacular scenery along the river, into a private park. They constructed a gate house, an attractive structure with two fireplaces, and three pavilions for picnics. They called it Hi-Pot-Lo Park, and welcomed tourists and church groups for pleasant summer time outings.

In the late 1950s, the Grand River Conservation Authority began negotiations with Edgar Harris for the purchase of the property. The deal was completed in 1962, 95 years after Edgar’s grandfather started the woolen business.

In 1963, the GRCA talked with a Toronto developer about converting the old mill into a restaurant, but the project fell through. The old mill, meanwhile, had become an attraction to vandals. Arsonists torched the long-neglected structure in 1967.

Following the fire, the GRCA recognized the heritage significance of the mill. Workmen reinforced and stabilized the remaining stone walls in 1968, cleaned out the mill race, and rebuilt the dam.

The following year the Rockwood park ranked second only to the Elora Gorge Park in popularity among the GRCA’s conservation areas. Some 40,000 visitors passed through the gates in 1969.

*This column was originally published in the Wellington Advertiser on Aug. 31, 2001.