FERGUS – Anyone living for more than a few years in Centre Wellington has likely heard of the Bill Beattie Band.

Born in 1938, and raised on a farm between Elora and Fergus, Bill Beattie was destined to become a farmer.

However, when his father passed at an early age, Beattie worked as a delivery driver for Howes and Reeves Limited. In later years, he worked in the oil business, delivering fuel and lubricants for Esso Imperial Oil.

From the time he was young, Beattie was fascinated with music, and based on his mother’s suggestion, took up piano lessons.

“I got along fairly well with the lessons, and I was inspired by a couple of other people that were exceptional, and I thought ‘those guys are good, I wonder if I could learn to do that?’” he said.

As it turned out, he could.

In his mid-teens, Beattie teamed up with a fiddle player around his age, hoping to get good enough to play at local schoolhouse dances.

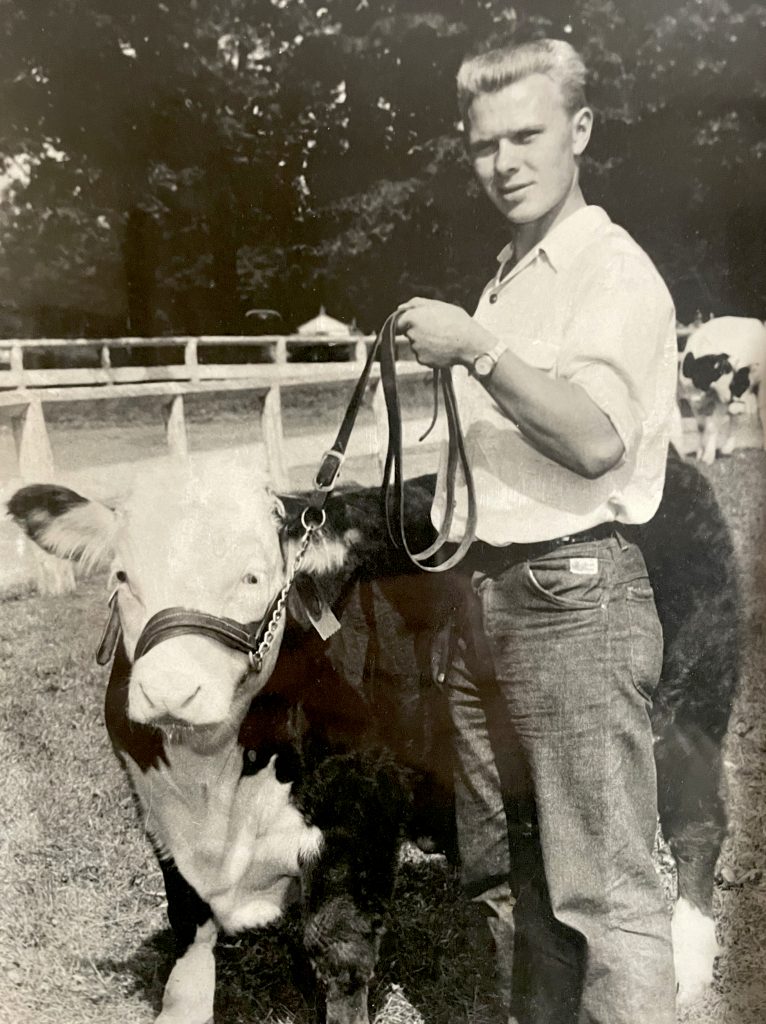

Beattie at age 17 as a member of the 4H calf club. Submitted photo

Tickling the ivories

They were a natural fit, and played together for two years, until about 1954.

“Another guy phoned me up who had a band (Watson’s Orchestra) that needed a pianist and asked if I would be interested,” Beattie said.

He played in Watson’s Orchestra for a number of years before performing with other musicians; the Bill Beattie’s Band gradually taking form.

“Over the years we’d have different people in the band. There were typically four or five of us and we were always looking for a bass player or some other role,” he said.

“I was on keyboard, and we had a fiddle player, bass player, drummer, and vocalist – we always had a female vocalist.”

The group’s many iterations played upwards of 50 country performances a year to audiences ranging from 100 to 200.

“They call it ‘classic country now,’ since it’s more of the older stuff. Back then it was new stuff,” Beattie said jokingly.

“We didn’t play anything original, just tunes that we wanted to learn that somebody else wrote. It was stuff that we’d hear on the radio or on TV.”

In recent years the band has leaned into Ray Price and Merle Haggard, but its inspiration comes from sources spanning decades.

“I never was into writing music,” Beattie added.

“I admire people that have that talent, but I never did and didn’t really care. There’s lots of good tunes out there to learn without writing any more.

“Getting out and playing at public dances was our main thrust.”

The Elora Legion was one of the band’s main venues, but it also frequented the Fergus Legion and Alma Community Centre, along with several festivals and retirement homes, including Highland Manor, Carresent Care, Heritage River and Wellington Terrace.

Couples dance at a live performance. Advertiser file photo

Moving on

Beattie said he decided to quit for three reasons: “I’m getting old, there aren’t many dances, and it’s been kind of dying out.”

“The crowd we played for 50 years ago are, unfortunately, either old or gone. There aren’t too many young people who are interested in the type of music or dancing that we were involved with.”

He added, “It’s an interesting thing: dancing used to be a very popular form of recreation for people going back over generations. Now it’s mostly just older people that still dance.

“When I was a kid, there were dances every place, all the time. That’s what people did for recreation before television, cell phones and a whole lot of other things.”

The COVID-19 pandemic helped bring the band’s end.

Though Beattie has played a few shows since, he ultimately saw an opportunity to play his final note.

“I was getting tired of lugging sound equipment around and all the work of travelling, setting up, doing a sound check and then having to gather everything up and truck it home. The novelty of doing that wore off,” he said.

Beattie reflected on a particular incident that happened “back in the day” while preparing for a dance at the Knights of Columbus, a once-popular hall for events.

“We were booked for a show and there’d been a meal first, so the hall was already full before our set. This was back before there were electronic keyboards and most public halls had an old piano,” he recalled.

“We got on stage, and I put my hands down on the keys and thought ‘Oh my goodness.’ The keys went down, the hammers went in, but that was it … they stuck, and they didn’t come back up. The piano was absolutely useless.

“I thought ‘Oh my gosh, here’s this major crowd waiting to dance, and we can’t do it.’ It was an absolute disaster.”

He continued, “As a farm boy, when something seized up, I’d get the oil can. I went back to the bar and asked the boys, ‘Is there any chance there’s an oil can in the hall?’ Well bless their soul, they found one.

“I went up, looked at the piano and thought ‘If I don’t do anything it won’t work, and if I ruin it, it won’t work, so I have nothing to lose.’

“Here’s this guy squirting oil at the all the hammers of the piano. I don’t know how many people thought I’d gone completely crazy, but guess what? It worked. We played the gig and it was successful.”

Giving back

Apart from years at the piano keys, Beattie has contributed to Centre Wellington and beyond by volunteering with the Boy Scouts and working with the Fergus Scottish Festival and Highland Games.

“They used to just call it the Highland Games back when it started after the war in 1946,” he said.

“Somebody in Fergus thought it’d be a good idea to celebrate Fergus’ Scottish heritage and history.”

Beattie joined the Fergus Chamber of Commerce in 1978 and helped form a committee that manages the event. He was president of the committee in 1995, and is still involved with it today.

While he was never a scout leader, he was part of the organization’s management and the fundraising team for Scouts Canada, organizing paper drives and getting his own son involved.

Volunteering for Scouts is something Beattie has always been proud to have been a part of.

He said he has many fond memories performing at dances over the years, and has become somewhat of a local celebrity for his contributions to the country music scene.

“I used to get a kick out of how we’d get a dance going, sitting up there on the stage, looking out to see the crowd floating by,” he said.

“If the floor was full, we knew we were doing a good job that night. The more the merrier,” he said.

“It was just so rewarding looking out and seeing everyone having a great time.”