Concentration camp survivor shares story of his early years

Fergus resident Walt Visser wants to recognize Erna Ouwens, the forgotten woman who nurtured him in the 1940s

INDONESIA – Walt Visser was born within the walls of a concentration camp in Indonesia in 1943, and he’s alive today thanks to the love and care of an Indonesian woman named Erna Ouwens.

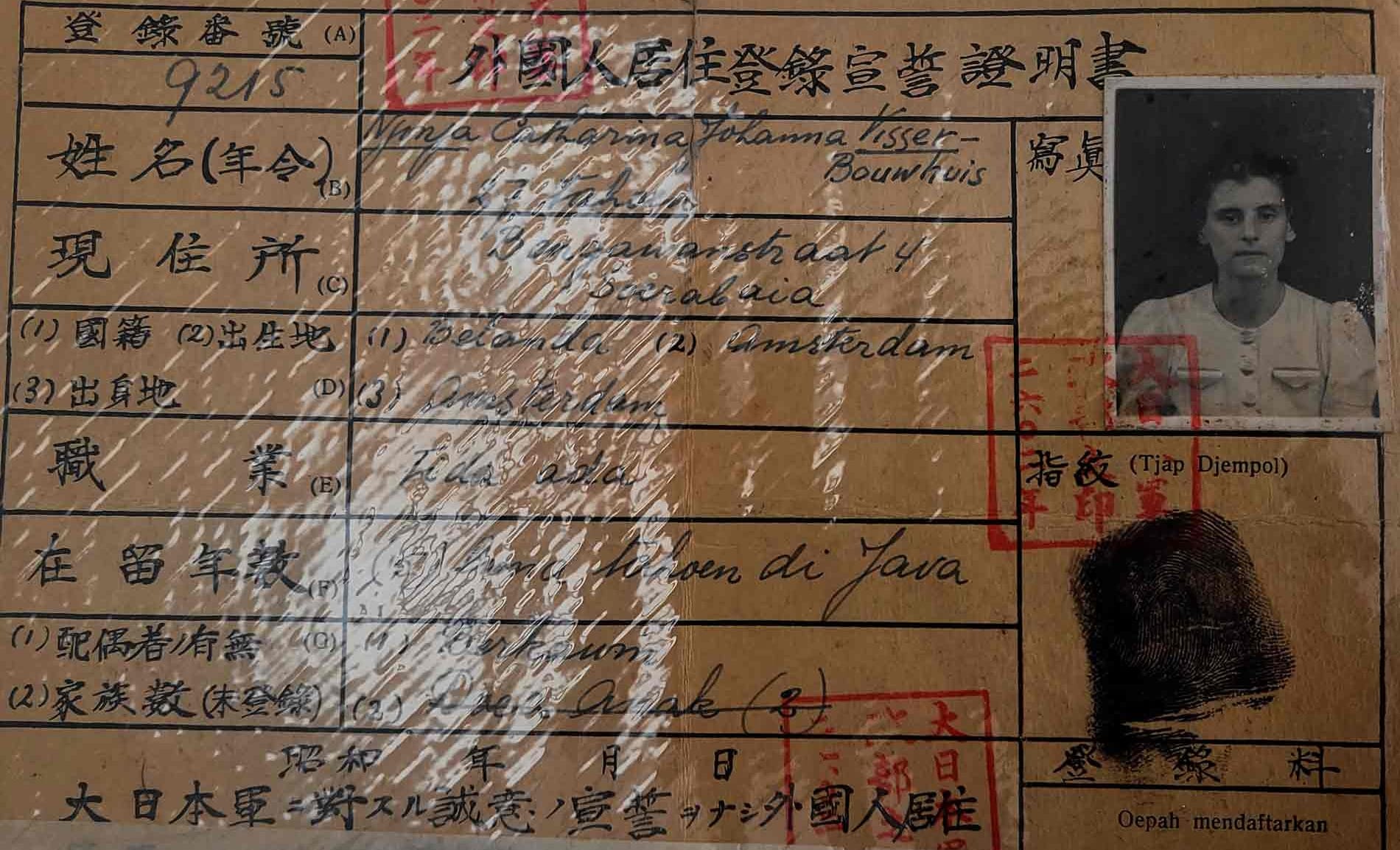

Sitting at a small table in his Fergus home, a photo album filled with letters, documents, drawings and photographs open in front of him, Visser shared his story.

It begins in 1936, when his mother Tina followed his father Tim by ship from Holland to Indonesia.

Tim was “quite well to do,” Visser said, and was connected to an international newspaper called Volkskrant.

Tim and Tina’s love story was written in the pages of that paper, but it’s not the one Visser wants to share.

In 1943, the Vissers and Ouwens were not yet connected.

Tim and Tina were living in East Java with their two children, Visser’s older siblings.

His mother was pregnant, and the couple went out for a motorcycle ride on July 15, with hopes of inducing labour, Visser said.

But Indonesia was under Japanese occupation, and the Vissers were arrested and taken to concentration camps – Tim to the Kalisosok Prison and Tina and the children to the Darmo Camp for women and children.

A week later, Visser was born in the camp.

He said he was unwell from the beginning, as he and his mother were malnourished. Before long he was removed from the camp and hospitalized.

Though there was a big red cross painted on the roof of the hospital, the building was bombed, and Visser said he was one of just two survivors: “a little old lady and me.”

A Japanese commanding officer saw him in the rubble, Visser said, “picked me up, and because of my red hair, took me home.”

The officer hired a “babu” – a nanny – to care for Visser. Her name was Erna Ouwens.

Visser said the man was “criticized by fellow officers for having a white kid in his home,” so before long, he told Ouwens to take the kid and go. She did, and cared for him for years.

Meanwhile, Visser’s parents were wondering what happened to their son.

After Japan surrendered in 1945, the Vissers were repatriated back to the Netherlands with their two eldest children, but not Walt.

“As far as they knew, I was killed in the hospital,” he said.

Inquiries through the Red Cross and children’s aid organizations came up dry, so the Vissers leaned on their connections through the newspaper to find information.

Ads were placed in papers and eventually someone recognized Walt.

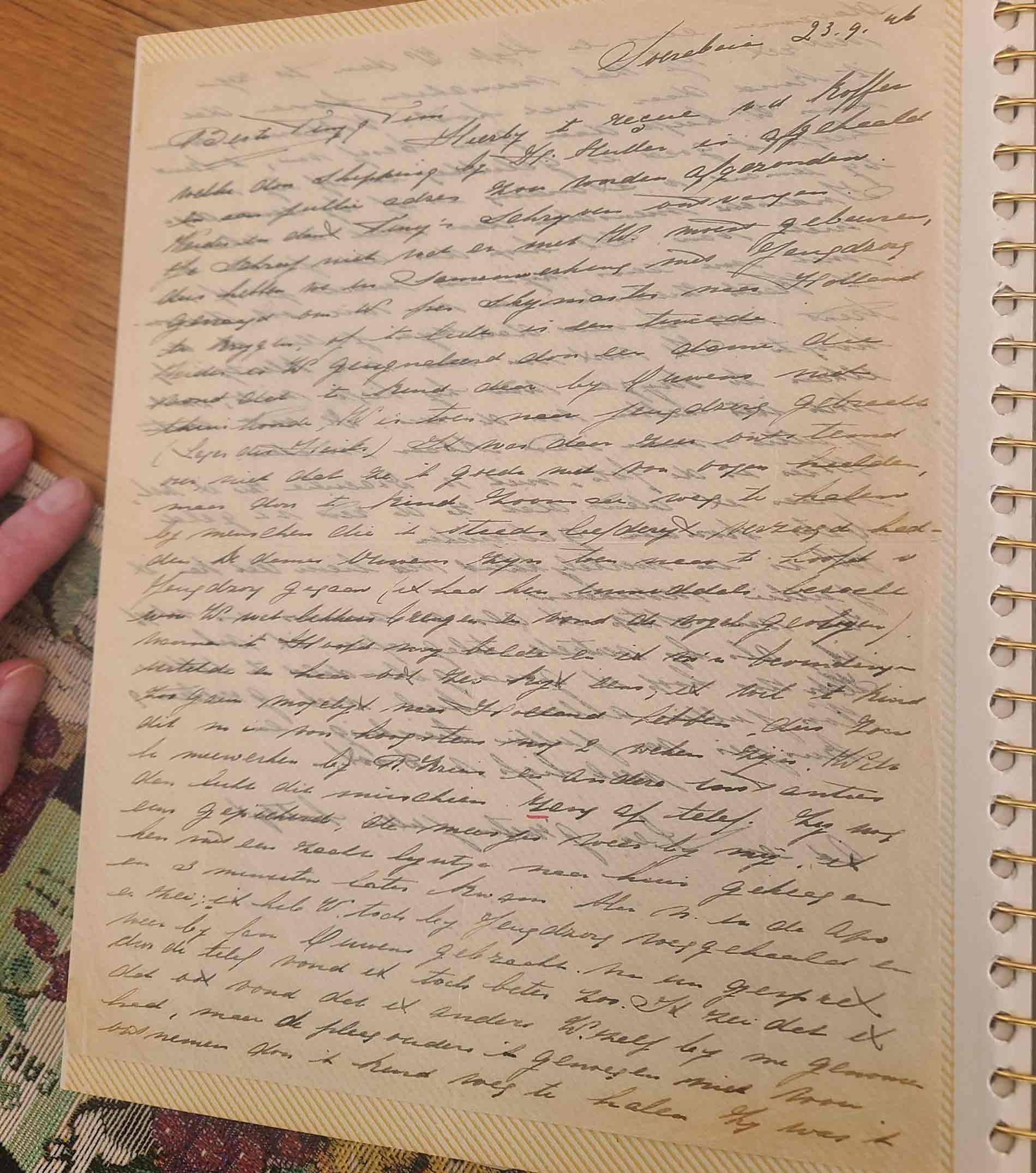

A friend of the Vissers visited him in the Ouwens’ home in Soerabaja, East Java. They wrote to his parents about what they saw.

“Your darling has been kept safe,” a translation of the letter states. “He looked very good, really cuddly, was well taken care of, no diaper rash. And he was wearing a cute playsuit.”

The Vissers’ friend said they offered to take Walt and return him to his parents, to which Erna held him close and said she “would not part with him as he was such a darling and we love him so.”

They wrote that the Ouwens “really love the child and each and every one is so good to him.”

“They are Indonesians. We would never take your children into these surroundings, but to take him away at this time appeared to be mean to me,” the translated letter states.

The local children’s aid society visited the Ouwens too, Visser said, and left him in their care.

“They didn’t have a legal reason to take me – I don’t mind that they didn’t,” he said.

Ouwens wrote to the Vissers, pleading with them to allow the boy to spend his childhood with her.

“We love him so much,” Ouwens wrote. “Walter also loves us very much. How terribly will he cry when he must leave us,” the translation of her letter states.

Ouwens said she was in a camp in Malang, East Java, when Visser came to live with her, “and he was more corpse than living body.

“He had dysentery and malaria, and no one wanted to touch him because he was so skinny and dirty … And his malaria kept coming back.

“But none of that matters anymore because we love him very much, and now he is fat and healthy.”

She asked the Vissers to consider allowing Walt to stay with her “until he comes of age, and then we could slowly introduce him to the fact that he belongs in Holland.”

Eventually, though, Ouwens was tricked into handing the boy over, in a move Visser finds “rotten.”

He became unwell again – at age three in October of 1946 – and Ouwens was persuaded to bring him to a Dutch medical centre where she was told he’d receive the best care, Visser said.

When they got to the centre Ouwens was not allowed inside – an official promised they’d bring Visser out after the appointment. “But they didn’t do that,” he said.

“They took me out the back door and put me on a ship.”

That ship, the MS Klipfontein, was bound for Holland and Visser never saw Ouwens again.

He wonders how long she sat outside the medical centre, waiting to bring him home. “She might have been on that doorstep a week,” he said.

Visser suspects his father, or his friends at the newspaper, paid a hefty price for his place on that ship, as it would take a lot to convince a sea captain to bring an unaccompanied young child on board for the five- to six-week voyage.

His story was told in a series of articles in the Volkskrant, Visser said, framed as a wonderful tale of a lost boy returning home.

By 1953, his father was editor of that newspaper.

Visser lived a successful life – he did three terms in the Canadian army in the ‘60s and ‘70s, studied psychology and Slavic history at Brandon University in Manitoba and sat on Centre Wellington municipal council.

But he never got to reconnect with Ouwens, and didn’t realize what a significant role she played in his childhood until he hashed out the details about a month ago.

Before then, he had been under the impression he’d lived with her for days, not years.

Visser said while he’s typically not a tender person, he feels shook by how Ouwens was treated after caring for him for years in a war-torn country.

“They shit on her,” he said. “Nobody ever thanked her.”

He acknowledges that his parents were in a tough position, but feels “people took advantage of being white and of working for a newspaper and of having power over brown people.”

Visser said he wants to share the story because of the state of the world.

“So many people are misused and abused and one of those people who did only good was treated that way – I think that should be known,” he said.

“It was three years that this woman had me, and the way they treated her was really very bad.”