The following is a re-print of a past column by former Advertiser columnist Stephen Thorning, who passed away on Feb. 23, 2015.

Some text has been updated to reflect changes since the original publication and any images used may not be the same as those that accompanied the original publication.

Through the 19th century and into the first years of the 20th, the economies of Fergus and Elora were tied closely to the processing and movement of agricultural products.

Elora, with its monthly cattle and grain market, had the larger share of the business before the 1870s, but was later overtaken by Fergus, led by the Monkland Oatmeal Mills and John Black, Centre Wellington’s major cattle and grain dealer in the 1890s.

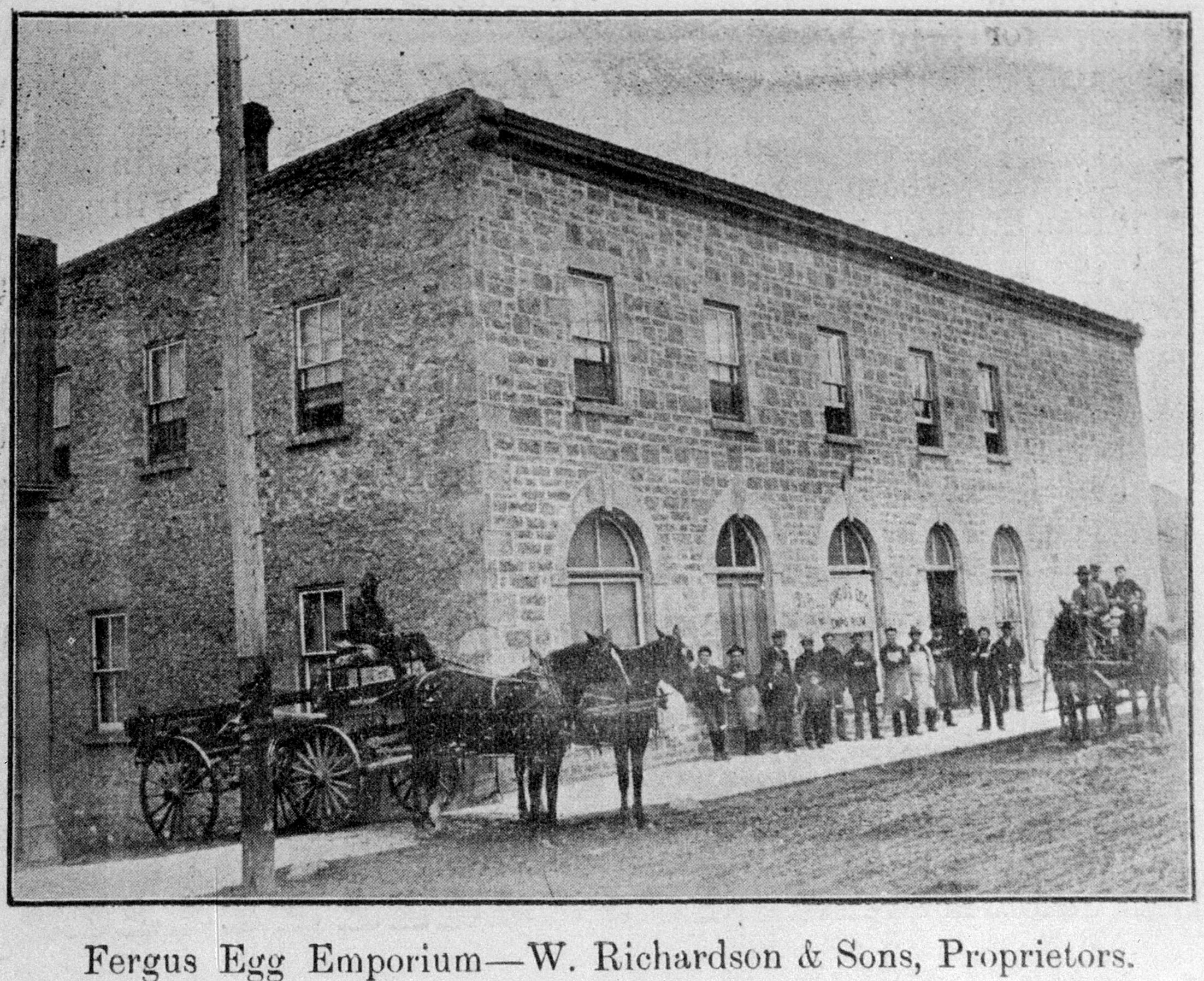

A third Fergus business of major significance to the agricultural sector was the egg processing plant, known by the sonorous title of the Fergus Egg Emporium.

This business had its origins in the late 1860s, when J.D. Wilson began buying butter and eggs in the Fergus area and shipping them to exporters based in Hamilton and Toronto. The business thrived, and J.D. was soon known as “Egg” Wilson.

In 1881, “Egg” Wilson bought property on the south side of St. Andrew Street, a short distance east of Tower Street. The building on this site, which still stands, appears to have been constructed in 1883: Wilson mortgaged the property for $3,000 in that year.

The building, which originally had five semi-circular windows on the front, is similar to many other St. Andrew Street structures, though it lacks the third floor and mansard roof that characterize Fergus commercial architecture of the early 1880s.

“Egg” sold the business in 1887 to D.D. Wilson of Seaforth, who for more than a decade had been known as the “Egg King of Canada.” (I have not discovered if the two men were related.)

D.D. Wilson had started his egg shipping business in Seaforth in 1867, and by 1880 he was shipping eight million eggs each year, most to the New York market. He was generally regarded as one of the country’s experts on eggs and poultry.

The 1881 Ontario Agricultural Commission listened to D.D. Wilson at great length, and his testimony makes fascinating reading for anyone interested in the development of poultry in Ontario.

Wilson believed that keeping a small number of hens could be a lucrative sideline for most farmers. He viewed the ideal flock as 50 or 60 hens; these could be fed scraps and other substances that would otherwise go to waste.

Wilson admired the Brown Leghorn breed, and had great hopes for Plymouth Rocks, then a new breed, which he believed could be used for both egg and meat production.

Though Wilson and a few others took great interest in breeding and improving poultry breeds, most farmers maintained flocks of what were often called common barnyard fowl. Egg production was seasonal, peaking in the spring and then tapering off through the summer and fall. Few farmers were able to maintain egg production through the winter.

The Fergus Egg Emporium became a major business under D.D. Wilson. By 1892, he was receiving 25,000 dozen eggs per week during the peak of the season in May. The eggs were graded and sorted, and then packed into barrels, with oat hulls for packing. The hulls, of course, came from Monkland Mills.

The barrel was then filled with a water and lime solution. Wilson would not reveal the formula he used. Later, a solution of sodium silicate, known as water glass, became the preferred preservative. A barrel normally held 70 dozen eggs.

D.D. Wilson sold the Fergus plant to W. Richardson and Son, of Walkerton, in 1893. Two sons, W.A. and D.W. Richardson had charge of the Fergus plant. During the 1890s, the United States became more protectionist, and the British egg market began to open up. Richardson exploited this new outlet, and shipped eggs to customers in British Columbia as well.

During the peak of the season in the spring Richardson candled 6,000 dozen eggs each day, checking for imperfections, and grading according to size. The west end of the building (which now houses the Fergus Tandoori Grill) contained cold-storage facilities. Richardson preferred to store a portion of the eggs and ship them by the carload late in the season to get the best price.

The Fergus Egg Emporium employed five wagons and teams, which visited farms and stores throughout the area, picking up eggs. Poultry keeping was generally regarded as a woman’s occupation, and many farm wives exchanged the eggs from their small flocks for groceries and dry goods at general stores. As well, a few farmers had begun to specialize in poultry by the 1890s; these had flocks numbering in the hundreds.

Using D.D. Wilson’s estimates that the average flock numbered about 60 hens, and assuming each bird laid 5 eggs per week, we can determine that about 1,400 farms in central Wellington supplied the Fergus Egg Emporium, with a total of about 85,000 laying hens.

Prices fluctuated seasonally, but generally averaged about 10 cents per dozen at the farm gate in the 1900 era. The 1993 equivalent would be in the $4.50 to $5 per dozen range, a price that now would certainly induce many farmers to take up poultry as a sideline (this would be $7 to $8 in 2019)

The plant itself employed, depending on the time of year, between 10 and 20 men and boys in the grading, packing and handling of the eggs. By the standards of the time this was a major business; during a busy month more than 1,250,000 eggs could pass through the building.

During the winter, the men and teams were employed harvesting ice and transporting it to the ice house that once stood to the rear of the stone building; the backyard also contained a livery stable for the horses and sheds for the wagons and barrel storage.

The loss of export markets during the First World War quickly ended the major market for the Fergus Egg Emporium. By this time, the North American market was changing as well.

Consumers preferred fresh eggs, when these became generally available, to preserved ones, and the Fergus Egg Emporium failed to establish itself in the new marketplace.

*This column was originally published in the Elora Sentinel on March 2, 1993.